🇺🇸🇮🇹 Bilingual content: English first, Italian follows

The Strait of Gibraltar, the ancient Pillars of Hercules, is the boundary of the known world within the Mediterranean. According to myth, the demigod Hercules placed two pillars on either side of the Strait, between the promontories of Calpe, Spain, and Abila, Africa. At its narrowest point, it measures only seven miles between Punta Marroquí in Spain and Punta Cires in Morocco. Traffic is significant, as it is a key route between Europe and Asia and one of the busiest in the world, with over 100,000 ships crossing it each year. Tangier is already in the Atlantic, and the fear of even unintentionally crossing the course of a supertanker or a large cruise ship had already passed, but traffic inbound from the Atlantic Ocean and outbound from the Mediterranean remains very high, even on the range of routes branching off from the “Pillars.”

The skipper checks the weather forecast for the Canary Islands, the next stop and refueling point before the Atlantic crossing. 740 miles by route, 237 miles separate us from the island of La Palma, the westernmost of the seven Canary Islands. Our hope is to be pushed by the tail end of the Portuguese trade winds, which blow from northeast to northwest along the Portuguese coast and have contributed substantially to the country’s maritime and commercial success, and the start of the true trade winds that, as they accompanied Admiral Christopher Columbus and his three caravels, will carry us downwind to the Caribbean islands.

In Italian trade winds sounds “alisei” and the name comes from the Latin root alis, meaning smooth, and partly determines their stable and moderate nature. They are cool, moist winds that blow in the Northern Hemisphere from northeast to southwest. They are caused by the horizontal pressure gradient, that is, the regular alternation of high-pressure belts (i.e., tropical zones) and low-pressure belts (equatorial zones), and are deflected westward by the Coriolis force, i.e., the effect of the Earth’s rotation and the low viscosity of the atmosphere. In English, they are called “Trade Winds” because they supported and enabled commercial shipping until a century ago.

We boldly leave the smelly and “smoky” mooring of the folkloristic Moroccan city, placing our trust and hope in the “regularity” of the Atlantic winds, counting on covering the 740 miles to La Palma in three or four days, given that the sailing should be super-fast, that is, broad reach, and CS&RB II Busnelli from a beam reach onward is lightning fast. But we know that in meteorology, regularity doesn’t exist.

Averages exist. Which are something else entirely, like Trilussa’s (XIX century poet from Rome) famous example of the chicken, where the average is one chicken per person, but a rich man eats two and a poor man none. Thus, with the help of a perverse Aeolus and the assistance of a mischievous Jupiter Pluvius, a localized storm is unleashed, with a minimum over the Canary Islands and winds blowing directly opposite, namely southwesterly winds, coincidentally right on our route. Of course…

“Excuse me, skipper, what did the weather forecast predict?” “Well… it didn’t predict a force 7 storm with southwesterly winds…” And once again, the age-old empirical practice of a moistened finger exposed to the wind and worried eyes scanning the horizon applies. So double reefs are taken to the mainsail, forestay, and double jib. The children are disappointed, feeling betrayed after all the promises of trade winds, downwind sailing, a relaxed life, and gentle rolling on the long ocean swells. As usual, we’re leaning 20 degrees, we’re lapped by the sea and the sky, and the CS&RB II Busnelli is struggling at its least efficient speed, with wide, very wide true angles. The dream of three or four days collides with the reality of making progress on the actual course of just 70 miles a day. Which makes... 10 days? Are you kidding? Fine, but the storm will end sooner. And yet, it keeps us in the game, literally, for a good week. After this upwind slog, of constant disappointments—”Where are we?”, “Hey, we should be here 380 miles away,” “What? Another 380 miles? Are we going forward or backward?”, “Adelante, Pedro, con juicio,” Antonio Ferrer, Grand Chancellor of Milan, said to his coachman in The Betrothed, the historical novel by Alessandro Manzoni.

This first, challenging week on the Atlantic is marked by numerous episodes of seasickness, but also, on the positive side, by the resumption of watchkeeping, which separates the conflicts and the two contenders and allows the skipper to concentrate on the route, navigation, and proper handling of the boat. The wet, upwind sailing makes the internal helmsman’s station appreciated, well protected by the Plexiglas dome, which provides a fairly good view of the sail plan, the sail trimming, at least during the day, and a glimpse of the sea off the bow. But the nicotine addict skipper doesn’t give up his nervous inhaling and puffing of Marlboro Reds, even inside the dome, which measures just 80 centimeters in diameter, where the helmsman’s head is located, sitting on a tilting seat with a footrest. This helmsman’s station has no door, but the opening it’s not large enough to vent the copious amounts of smoke from the pack of Marlboro Reds consumed each shift. With a hand fan and a small battery-powered fan, the next helmsman tries to bring some fresh air into that smoky bubble, to survive...

Finally, after a week of sailing close-hauled, the dark outlines of the first Canary Islands appear on the horizon. There are seven islands, all of volcanic origin, and they form an autonomous community of Spain. They extend just north of the 28th parallel, at the same latitude as Florida and the Bahamas. We chose to land on La Palma, the westernmost of the Seven Sisters—not to be confused with Las Palmas, the capital of Gran Canaria, which is with Tenerife the most popular destination by the crowds of Central and Northern European retired tourists seeking warmth even in winter—because it is quieter and more sheltered from the passengers of the jumbo jets that swarm the two larger islands. The islands were named Canary Islands (from the Latin canis, “dog”) for the large number of wild dogs, ancestors of the modern-day Perro Majorero, from which the Canarian Presa Canario and the Canarian Dogo originated, which once populated the archipelago. However, the presence of canaries is also conspicuous, as are parrots, which enliven the island’s arboreal flora with their songs and sounds.

A stopover becomes essential because the trusty 49-horsepower Perkins 4.108 has a problem and is noticeably running on three cylinders, making port maneuvers particularly complicated. The skipper had wanted to disembark the more powerful 135-horsepower Perkins for fuel economy reasons, thus doubling the engine’s range, but at the expense of performance, given that the CS&RB II Busnelli displaces 25 tons and the 4.108’s fifty horsepower is frankly too little. Fortunately, this engine is so popular among fishermen and workboats on the islands that replacing the injector and adjusting it by mechanic Pedro is a quick and minor task. After a couple of days of enjoying “papas con mojo picón,” potatoes with a typical spicy sauce made of paprika, garlic, cumin, oil, and vinegar, and “cocido canario,” a stew of meat with chickpeas and vegetables, the hateful weather system with its force 7 southwest winds finally passed. Finally, the long-awaited trade winds blow strong and embracing, with their 15-25 knots of wind power, ready to carry us across the “Great Ocean Sea,” which owes its name to Greek mythology, a reference to the Titan Atlas. In ancient times, the ocean was called the “Atlas Sea” or “Atlantis Sea” because it was believed the Titan supported it. A roughly calculated 2,500 nautical miles await us on course 240 to reach Barbados, the easternmost island of the Lesser Antilles, or West Indies in English. Inexplicably, in Italy, you often hear the island’s name pronounced in the plural, “The Barbados.” There’s only one island, the least mountainous of the large arc-shaped archipelago of volcanic origin that extends from Grenada in the south to the British Virgin Islands in the north.

Enjoyed this article? Share it with someone who would love it too!

There’s great euphoria among the crew. For the skipper, it’s almost routine. This is the second Atlantic crossing after the one he completed on the Arpege Niña Boba in 1969 with his friend Carlo Mascheroni, Paolo’s older brother. After his participation in the first edition of the Whitbread Round the World Race in 1973, commanding the CS&RB I, in which he sailed the Atlantic north-south, these few 2,500 miles, carried by the gentle trade winds, are a “sinecure”. Carla is also an ocean sailor. She was christened with two Whitbread legs and the Chica Boba trip from Italy to Plymouth, which I was also on. For everyone else, it’s an exciting first.

Head 255, because it’s combined with a broken rhumb line to create a great circle composed of fixed route segments for at least a couple of days at a time. It’s well known that a constant route that intersects the meridians at the same angle is not the shortest route between two distant points on a sphere, while the shortest line connecting two points on a sphere is a portion of the great circle, obtained by intersecting the surface of the sphere with a plane passing through the center. In navigation, assuming the Earth is spherical, a vessel navigates by an orthodrome when, in going from one point to another on the Earth’s surface, it traverses the shortest arc of a circle connecting them. This arc has the characteristic of crossing all meridians at different angles, along a great circle. This is unlike the rhumb line, which instead cuts all meridians at the same angle, but compared to the rhumb line, which offers a significant saving in travel time, especially over long distances.

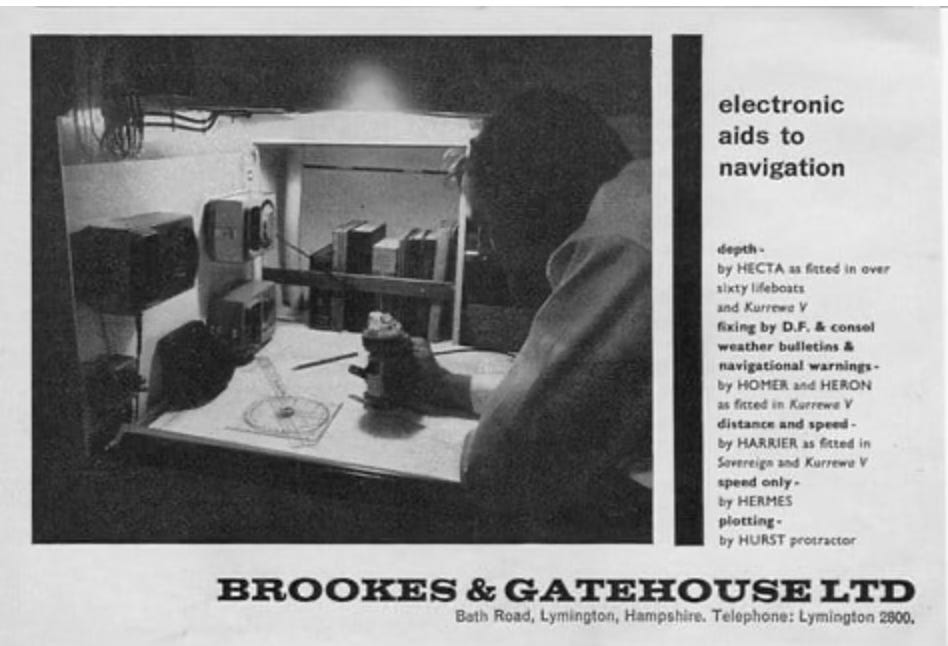

Along with the mainsail, we hoist the forestay and the fisherman sail between the two masts, and at the bow the skipper immediately wants to hoist the spinnaker. The kit includes three: a light and medium one of equal size, and the heavy one is the smallest. We opt for the medium one, given the trade winds of around 15 knots. CS&RB II Busnelli sets off at a gallop on the ocean’s swells. They are 3-meter waves, hundreds of meters long. As it descends from the crest to the trough, the schooner almost surfs. The skipper and crew shout in unison with excitement when the white needle on the Brookes & Gatehouse analog speedometer hits 12 knots. The sky is dotted with small clouds, white puffs scattered across the blue, confirming the stability of the humid trade winds. But every now and then they gather, and form into a kind of thunderstorm, forming a large gray cloud that doesn’t necessarily rain, but increases the wind speed, sometimes up to 30 knots. It’s the squall.

It lasts a few minutes. It’s typically a product of atmospheric instability, in which a sharp temperature contrast or pressure gradient causes cold, dense air to rapidly descend from a cloud. The squall requires a very rapid reduction in sail. “Lower the spinnaker. Lower the fisherman.” We remain with full mainsail and forestay, good for all winds. With the waves still increasing in height and length, the boom’s luff often touches the water. I suggest using a “half-reef,” that is, hauling in the luff on the first hand without lowering the halyard and hooking the relative tack point. The boom rises significantly, the surface area decreases slightly, and the luff’s “dive” is resolved. Once the squall has passed, we hoist the spinnaker again, abandoning the fisherman, which in reality conflicts with the spinnaker. Good speeds are maintained at between 9 and 10 knots.

The atmosphere on board is calm. The watches maintain separation of conflicts and disagreements. Off-duty, the skipper appears to comfort each watch, honing his magical arts of diplomacy and peacemaking. The fixed appointment is at noon to determine the height line, or the ship’s position with the sextant. He’s good at it; he manages to keep the sextant reading steady despite the pitching and rolling, while I’m tasked with reading the exact time when that angle of the sun at its zenith with the horizon gives us our position on the meridian we’re crossing. I don’t know how to do it; I’m practicing, but I leave the honor and burden of the precise point to the skipper. We even tried at night with the stars, but they’re too small, and even CS&RB II

Busnelli is too shaky to frame a Sirius, an Aldebaran, or a Rigel, which, despite being the brightest stars, are microscopic dots in the immense black sky.

Halfway through the crossing, an accident occurs with the spinnaker. Suddenly, the halyard breaks, and we pass over the large spherical sail that fell into the water at the bow at 10 knots. Only shreds remain. We would have to change the halyard tension every day by lowering and raising it in a range of one meter so as not to make the halyard cable work on the block always in the same spot. We learn from our mistakes, but in the meantime, we’re one spinnaker down. We hoist the heavy one, a little smaller, yet perhaps more effective than the medium one. And after 14 days of trade winds, long waves, flying fish that sometimes landed unknowingly on deck, a blue whale that accompanied us on our route for almost two hours at the same speed, several squalls and sail changes, the low, hilly shape of Barbados appears on the horizon. We’ve made it. It’s March 5th, Ciri’s birthday.

I give him the island, but without the package.

by Roberto Franzoni

(English translation and editing: Elena Paxia)

(Italian Follows)

Subscribe to Yacht Lounge – it’s free. One click and you’ll discover a world of authentic stories, beyond the ordinary.

✦ To be continued in the next episode…

CS&RB II – Le Canarie e la traversata atlantica.

Lo Stretto di Gibilterra, le antiche Colonne d’Ercole, confine del mondo conosciuto all’interno del Mediterraneo. Secondo il mito il semidio Ercole pose due colonne ai lati dello Stretto, tra i promontori di Calpe, in Spagna, e di Abila, in Africa. Nel punto più stretto misura solo 7 miglia tra Punta Marroquí in Spagna e Punta Cires in Marocco. Il traffico è cospicuo essendo una rotta chiave tra Europa e Asia e una delle più trafficate al mondo, con oltre 100.000 navi che lo attraversano ogni anno. Tangeri si trova già in Atlantico e le paure di intersecare, anche involontariamente, la rotta di una superpetroliera o di una nave da crociera di notevoli dimensioni era già passato, ma il traffico in avvicinamento dall’oceano Atlantico e quello in uscita dal Mediterraneo rimane molto elevato anche nel ventaglio di rotte che si diramano dalle “Colonne”.

Lo skipper consulta il meteo per la rotta verso le Canarie, prossimo punto di appoggio e di rifornimenti prima della traversata atlantica. 740 miglia per rotta 237 ci separano dall’isola de La Palma, la più occidentale delle sette isole canarine. La nostra speranza è di essere sospinti dalla coda degli alisei portoghesi, che soffiano tra nordest e nordovest lungo la costa lusitana e hanno contribuito sostanzialmente alla fortuna marittima e commerciale del paese, e l’avvio degli alisei veri e propri che, come accompagnarono l’ammiraglio Cristoforo Colombo e le sue tre caravelle, ci sospingano al lasco fino alle isole dei Caraibi.

ll nome degli alisei deriva dalla radice latina alis, che significa liscio, e in parte ne determina il carattere stabile e moderato. Sono venti freschi e umidi, che spirano nell’emisfero boreale da nord-est verso sud-ovest. Sono causati dal gradiente barico orizzontale, cioè dalla regolare alternanza delle fasce di alta pressione (ovvero quelle tropicali) e quelle di bassa pressione (zone equatoriali) e vengono deviati verso ovest dalla forza di Coriolis, ovvero per effetto della rotazione terrestre e della scarsa viscosità atmosferica. In inglese i chiamano “Trade Winds” perché hanno sostenuto e consentito la navigazione commerciale fino a un secolo fa.

Baldanzosamente lasciamo l’ormeggio odoroso e “fumoso” della folkloristica città marocchina poggiando fiducia e speranze sulla “regolarità” dei venti atlantici, contando di coprire le 740 miglia per La Palma in tre-quattro giorni, dato che l’andatura dovrebbe essere super portante, ovvero gran lasco, e CS&RB II Busnelli dal traverso in poi è un fulmine. Ma si sa che in meteorologia la regolarità non esiste. Esistono le medie. Che sono altra cosa, come il famoso pollo di Trilussa, per cui la media è un pollo a testa, ma un ricco ne mangia due e un povero nessuno. Così con lo zampino di un perverso Eolo e il contributo di un dispettoso Giove Pluvio si scatena una burrasca localizzata con minimo proprio sulle Canarie e venti esattamente opposti, ovvero sudovest, guarda caso proprio sulla nostra rotta. E ti pareva…

“Ma scusa skipper cosa aveva pronosticato il meteo?” “Mah… non aveva previsto una burrasca forza 7 con venti da sudovest…” E ancora un a volta vale l’antica pratica empirica del dito umettato ed esposto al vento e degli occhi preoccupati che scrutano l’orizzonte. Allora due mani di terzaroli alla randa, vela di strallo e fiocco due. I piccoli sono delusi, si sentono traditi dopo tutte le promesse di alisei, di andature portanti, di vita rilassata, di dolci rollii sulle onde lunghe dell’oceano. Siamo come al solito sbandati 20 gradi, siamo bagnati dal mare e dal cielo e il CS&RB II Busnelli arranca nella sua andatura meno efficiente, con angoli reali ampi, molto ampi. Il sogno dei tre-quattro giorni si scontra con la realtà di un avanzamento in rotta reale di scarse 70 miglia al giorno. Il che fa… 10 giorni? Ma scherziamo? Va bene, ma la burrasca finirà prima. E invece ci tiene in ballo, nel vero senso del termine, una buona settimana. Dopo questo sbattimento di bolina, di delusioni continue, “dove siamo?”, “eh, dovremmo essere qui a 380 miglia”, “cosa? Ancora 380 miglia? Ma stiamo andando avanti o indietro?”, “adelante, Pedro, con juicio, diceva Antonio Ferrer, gran cancelliere di Milano, al suo cocchiere nei Promessi Sposi”.

Questa prima sofferta settimana atlantica è segnata da numerosi episodi di mal di mare, ma in positivo anche dalla ripresa delle guardie, che separano i contrasti e le due contendenti e consentono allo skipper di concentrarsi sulla rotta, sulla navigazione e sulla buona conduzione della barca. La navigazione bagnata di bolina fa apprezzare la timoneria interna ben protetta dalla cupola in plexiglas che lascia vedere abbastanza bene il piano velico, la regolazione delle vele, almeno di giorno, e uno scorcio di mare a prua. Ma lo skipper tabagista non rinuncia al suo nervoso aspirare e sbuffare fumo di Marlboro rosse nemmeno all’interno della cupola, che misura solo 80 centimetri di diametro, dentro cui si trova la testa del timoniere, seduto su un sedile basculante con poggiapiedi. Il loculo non ha porta, ma un’apertura a giorno, tuttavia non sufficiente a sfogare la fumeria abbondante del pacchetto di Marlboro rosse consumato a turno. Con un ventaglio e un piccolo ventilatore a batteria il timoniere successivo cerca di apportare un po’ di aria fresca in quella bolla affumicata.

Stai apprezzando questo articolo? Condividilo con chi potrebbe amarlo quanto te!

Finalmente dopo una settimana di bolina compaiono all’orizzonte i profili scuri delle prime Canarie. Le isole sono sette, tutte di origine vulcanica, e formano una comunità autonoma della Spagna. Si estendono poco più a nord del 28º parallelo, ovvero alla stessa latitudine della Florida e delle Bahamas. Abbiamo scelto di approdare a La Palma, la più occidentale delle sette sorelle, da non confondere con Las Palmas, capitale di Gran Canaria, con Tenerife la più frequentata dalle frotte di turisti centro e nord europei in pensione in cerca di tepori anche invernali, perché più tranquilla, più al riparo dai passeggeri dei Jumbo che affollano sciamando le due isole maggiori. Le isole vennero battezzate Canarie (dal latino canis, “cane”) per il gran numero di cani selvatici, antenati dell’attuale perro majorero dal quale derivano in parte il cane da presa canario e il dogo canario, che popolavano l’arcipelago. Tuttavia è cospicua anche la presenza di canarini, ma anche di pappagalli, cha allietano di canti e suoni la flora arborea isolana.

L’approdo diventa indispensabile perché il fedele Perkins 4.108 di 49 cavalli ha un mancamento e funziona vistosamente a tre cilindri, rendendoci le manovre in porto particolarmente complicate. Lo skipper aveva voluto sbarcare il più poderoso Perkins di 135 cavalli per ragioni di consumo, raddoppiando così l’autonomia del motore, ma a scapito delle prestazioni, dato che CS&RB II Busnelli disloca 25 tonnellate e la cinquantina di cavalli del 4.108 sono francamente pochini. Fortunatamente il motore è così diffuso tra i pescatori e le barche da lavoro delle isole che la sostituzione dell’iniettore e la sua regolazione da parte del meccanico Pedro è intervento rapido e di poco conto. Dopo aver gustato per un paio di giorni “papas con mojo picón”, patate con la tipica salsa piccante a base di paprica, aglio, cumino, olio e aceto e il “cocido canario”, bollito di carne con ceci e verdure, terminata l’odiosa perturbazione con relativo vento forza 7 da sudovest, finalmente gli agognati alisei soffiano robusti e avvolgenti con i loro 15-25 nodi di energia eolica, pronti a spingerci al di là del “Gran Mare Oceàno”, che deve il suo nome alla mitologia greca, in riferimento al Titano Atlante. Nell’antichità, l’oceano era chiamato “mare di Atlante” o “mare di Atlantide” perché si credeva che il Titano lo sorreggesse. Ci aspettano più o meno mal contate 2.500 miglia per rotta 240 per approdare a Barbados l’isola più orientale delle Piccole Antille, o West Indies in inglese. Inspiegabilmente in Italia spesso si sente pronunciare il nome dell’isola al plurale “le Barbados”. L’isola è una sola, è la meno montuosa del grande arcipelago ad arco di origine vulcanica che si estende da Grenada, a sud, alle British Virgin Islands, a nord.

Una grande euforia tra l’equipaggio. Per lo skipper è quasi routine. È la seconda traversata atlantica dopo quella effettuata sull’Arpege Niña Boba nel 1969 con l’amico Carlo Mascheroni, fratello maggiore del nostro Paolo. Dopo il primo giro del mondo in regata nella prima edizione della Whitbread Round the World Race del 1973 al comando del CS&RB I in cui ha percorso l’Atlantico in rotta nord-sud, queste poche 2.500 miglia sospinte dai dolci alisei sono una sine cura. Anche Carla è una navigatrice oceanica battezzata con due tappe della Whitbread e la navigazione col Chica Boba dall’Italia a Plymouth, in cui c’ero anch’io. Per tutti gli altri è un’emozionante prima volta.

Prua 255, perché combinata in una lossodromica spezzata per ottenere una ortodromica composta da segmenti di rotta fissa per almeno un paio di giorni alla volta. Si sa che la rotta costante che interseca i meridiani con lo stesso angolo non è la rotta più breve fra due punti distanti di una sfera, mentre la linea più breve che permette di congiungere due punti su una sfera è costituita da una porzione di circonferenzamassima, ottenibile intersecando la superficie della sfera con un piano passante per il centro. In navigazione, considerando la Terra di forma sferica, un’imbarcazione naviga per ortodromia quando, nell’andare da un punto a un altro della superficie terrestre, percorre l’arco di circonferenza minimo che li congiunge, che ha la caratteristica di attraversare tutti i meridiani con angoli diversi, lungo un cerchio massimo, a differenza della lossodromia, che invece taglia tutti i meridiani con lo stesso angolo, ma rispetto alla quale vi è un sensibile risparmio di percorso, in particolare sulle lunghe distanze.

Insieme alla randa issiamo tra i due alberi la vela di strallo e il fisherman e a prua lo skipper vuole subito issare lo spinnaker. Il corredo ne conta tre, leggero e medio di uguale dimensione e il pesante più piccolo. Optiamo per il medio, dato un aliseo sui 15 nodi. CS&RB II Busnelli parte al galoppo sui cavalloni dell’oceano. Sono onde da 3 metri, lunghe centinaia. In discesa dalla cresta al cavo la goletta quasi surfa. Skipper ed equipaggio gridano d’entusiasmo in coro quando la lancetta bianca dell’indicatore di velocità analogico Brookes & Gatehouse tocca i 12 nodi. Il cielo è costellato di nuvolette, batuffoli bianchi sparpagliati nell’azzurro che confermano la stabilità degli umidi alisei. Ma ogni tanto si concentrano, si assommano e si costituiscono in una specie di temporale formando un nuvolone grigio che non necessariamente scarica della pioggia, ma fa salire la velocità del vento anche fino a 30 nodi. È lo squall, in italiano si tradurrebbe in burrasca, ma non rende l’idea. Dura pochi minuti. È tipicamente un prodotto dell’instabilità atmosferica, in cui un forte contrasto di temperatura o un gradiente di pressione fa sì che l’aria fredda e densa scenda rapidamente da una nuvola. Lo squall impone una rapidissima riduzione di velatura. “Ammaina lo spi. Ammainiamo il fisherman”. Restiamo con tutta randa e vela di strallo, buona per tutti i venti. Con le onde che aumentano ancora di altezza e lunghezza spesso la varea del boma tocca l’acqua. Propongo di prendere una “mezza mano”, cioè cazzando la borosa della prima mano senza ammainare drizza e agganciare il punto di mura relativo. Il boma si alza di molto, la superficie si riduce di poco e il “tuffo” della varea è risolto. Passato lo squall issiamo di nuovo lo spinnaker rinunciando al fisherman che in realtà con lo spi confligge. Si mantengono sempre buone velocità tra i 9 e i 10 nodi.

Il clima a bordo è tranquillo. Le guardie mantengono la separazione dei conflitti e dei contrasti. Fuori turno è lo skipper che compare a confortare ogni guardia, affinando le sue arti magiche di diplomazia e pacificazione. Appuntamento fisso è il mezzogiorno per la determinazione della retta d’altezza, ovvero il punto nave con il sestante. Lui è bravo, riesce a fissare la lettura del sestante nonostante rollio e beccheggio, mentre io ho l’incarico di leggere l’ora esatta in cui quell’angolo di sole allo zenith con l’orizzonte ci dà la posizione sul meridiano che stiamo attraversando. Io non lo so fare, mi sto esercitando, ma lascio l’onore e l’onere del punto preciso allo skipper. Abbiamo provato anche di notte con le stelle, ma sono troppo piccole e anche CS&RB II Busnelli è troppo ballerino per riuscire a inquadrare un Sirio, un’Aldebaran o un Rigel, che pur essendo le stelle più luminose sono dei puntini microscopici nell’immenso cielo nero.

A metà traversata capita un incidente allo spinnaker. Improvvisamente si rompe la drizza e sulla grande vela sferica caduta in acqua a prua passiamo sopra a 10 nodi. Ne rimangono solo brandelli. Avremmo dovuto cambiare tensione della drizza ogni giorno abbassandola e rialzandola in un’ampiezza di un metro per non far lavorare il cavo della drizza sul bozzello sempre nello stesso punto. Sbagliando si impara, ma intanto abbiamo uno spinnaker in meno. Issiamo il pesante, un po’ più piccolo, tuttavia forse più efficace del medio. E dopo 14 giorni di alisei, onde lunghe, pesci volanti a volte atterrati inconsapevolmente in coperta, una balena azzurra che ci ha accompagnato in rotta per quasi due ore, diversi squall e cambi di vele, all’orizzonte compare la sagoma bassa a collinosa di Barbados. Ce l’abbiamo fatta. È il 5 marzo, il compleanno di Ciri. Gli regalo l’isola, ma senza pacchetto.

by Roberto Franzoni

Iscriviti a Yacht Lounge, è gratuito. Un click ti apre un mondo di racconti autentici, lontani dai soliti schemi.

✦ Continua nella prossima puntata…